In Ireland, roughly 1 in 500 births are to babies with Down Syndrome. That is one of the highest rates in Europe. In the Rotunda Hospital, we see between 20 and 25 babies with Down Syndrome born every year. It is an important condition that affects many people and their families in Ireland we are dedicated to investing research in.

In a recent study in the Hospital that looked back at babies born with Down Syndrome over the last 5 years, we found that the majority of babies with a diagnosis of Down Syndrome ended up being admitted to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. The study looked at around 120 babies born with a Down Syndrome diagnosis, and found that over 80% of those babies were admitted into our Unit. You can read this study here.

Some babies were admitted straight away, after problems were diagnosed before or just after the baby was born, but the majority of cases were admitted after they had problems feeding or had a low oxygen levels in their blood.

All babies with Down Syndrome are screened for structural problems with the heart – about 50% of babies with Down Syndrome will have a structural abnormality with the heart and this needs prompt referral to our cardiology colleagues for surgical repair down the line.

The other biggest reason for a baby having low oxygen levels that we have found, other than structural heart disease, is actually the high pressure in the lungs, which is the focus of our research with these babies over the next few years.

We found that in babies with Down Syndrome, the transition whereby the blood vessels in the lungs which are usually closed up on delivery and open up slowly after birth doesn’t happen as smoothly. This is what we call pulmonary hypertension. The below video by the HRB Mother and Baby Clinical Trial Network explains what happens during this transition.

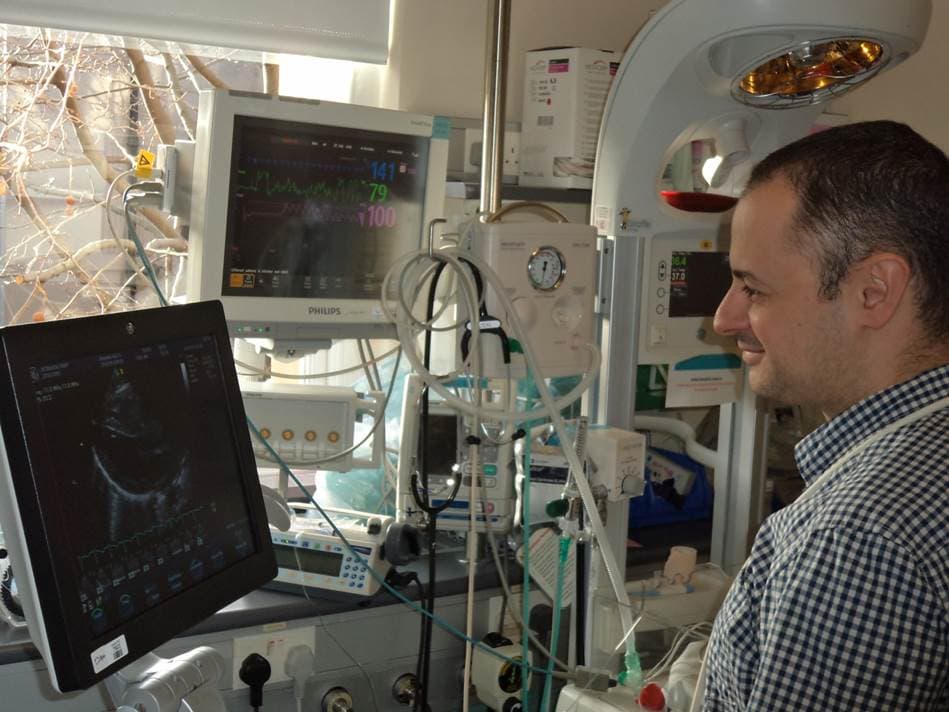

Prof Afif El-Khuffash, Consultant Neonatologist, in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

We use a technology called echocardiography, which is an ultrasound technique used to assess the function of heart muscles.

With echocardiography, we examine the right side of the heart. The right pumping chamber pumps blood into the lungs, and so we can derive what is happening in the blood vessels in the lungs from how the right side of the heart is behaving. From this, we can estimate how high the pressure in the lungs is – it should be quite low to allow blood to flow through the lungs freely, but in babies with this condition, it may be much higher than normal. We can see the right side of the heart struggling sometimes to pump blood against this high pressure in the lungs.

We were really struck by how many of these babies had pulmonary hypertension – much higher than the literature reported. Up until recently, the scientific literature showed that this is only a problem in 5% of babies, however recent research that we have published in the Rotunda has found that it can be as common as up to 50% of these babies. It is a problem that has been under-recognised.

We don’t know what happens to the pulmonary hypertension in those babies in the long run. This is one of our research endeavours.

We recently received a grant from the Health Research Board and the Children’s Medical Research Foundation which will allow us to follow all babies born with this condition in the three maternity hospitals in Dublin, and then we will call them back at 6 months, a year and 2 years, to do follow up scans.

We’re hoping to see how common the condition is, how long does it persist for, and whether it contributes to other conditions the baby may encounter over the first 2 years of life, and that would include problems with breathing and chest infections. We’re going to also see whether it is as common as we think it is. After that, we will try to target these babies and offer them treatment earlier to try to prevent the progress of the condition.

We hope that once we finish our research that we will have a strong case for pulling more resources into keeping closer follow-ups on these babies much earlier. That is the ultimate aim – To identify early and treat it early. This would hopefully reduce the incidences of hospital admittance with chest infections and reduce the complications associated with breathing and the lungs – and hopefully that will improve the quality of life for these children down the line.